Under Four Eyes

Torpedo Factory Art Center

Post-Graduate Residency

Alexandria, VA

What can the body hold that the archive cannot?

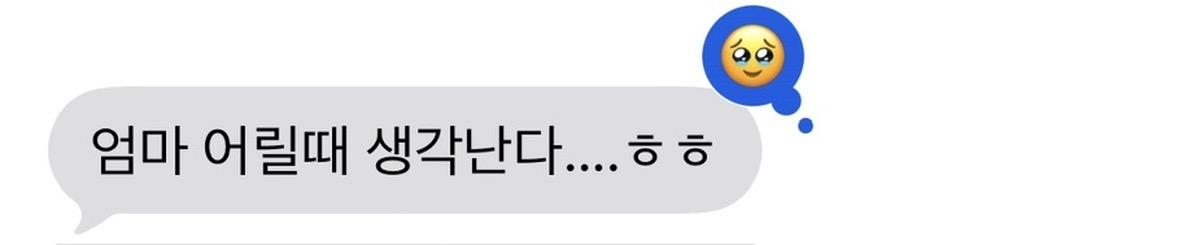

Under Four Eyes is a decentralized, embodied counter-archive project that gathers oral histories, field recordings, and rituals centered on intergenerational knowledge exchange.

Embodied that insists on movement and shape —gesture, ritual, and the struggle to remember as legible and valid modes of preservation.

The project takes its name from a German idiom—“unter vier augen”—which refers to private, intimate exchange between two people. Rooted in grassroots organizing methodologies, I’m interested in the archive that uses one-on-one conversation as both an artistic form and survival strategy.

And within this form I’ve been asking: What does it mean to pass down knowledge in hushed tones? How do we teach our communities to safeguard artists’ work during crises, outside institutional spaces—through neighbors, friends, and family?

During my time at the Torpedo Factory Post-Grad residency, the studio is transformed to mirror my umma’s tailor shop as I work through another form of soft mending, not with clothes but memory.

Torpedo Factory Art Center

Post-Graduate Residency

Alexandria, VA

What can the body hold that the archive cannot?

Under Four Eyes is a decentralized, embodied counter-archive project that gathers oral histories, field recordings, and rituals centered on intergenerational knowledge exchange.

Embodied that insists on movement and shape —gesture, ritual, and the struggle to remember as legible and valid modes of preservation.

The project takes its name from a German idiom—“unter vier augen”—which refers to private, intimate exchange between two people. Rooted in grassroots organizing methodologies, I’m interested in the archive that uses one-on-one conversation as both an artistic form and survival strategy.

And within this form I’ve been asking: What does it mean to pass down knowledge in hushed tones? How do we teach our communities to safeguard artists’ work during crises, outside institutional spaces—through neighbors, friends, and family?

During my time at the Torpedo Factory Post-Grad residency, the studio is transformed to mirror my umma’s tailor shop as I work through another form of soft mending, not with clothes but memory.

May 10, 2025

what is something you always wished I had asked and knew about you?

Goethe Institut x Thomas Mann House LA

USC Libraries, the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research

Washington, D.C.

I was invited by the Goethe Institut to present my floral sculpture series for an event called “An Appeal to Reason” inspired by the life and influence of Thomas Mann as a lens that rooted conversations around the current state of democracy, importance of freedom of expression, and the role of artistic intervention.

what is something you always wished I had asked and knew about you? is a floral sculpture series that confronts how we hold and carry memory in the diaspora through cocoji — a fading practice of floral arranging in Korea lost during a time of occupation and war.

The figures in the series includes the last remaining photographic archives of my family originally from the Gwangju region of Korea. A region known for the student-led demonstrations in their fight for democracy against the coup of Chun Doo-hwan in 1980.

The gidung table crafted by artist Jeffrey Yoo Warren is built around a hanok joint using the same woodworking technique that holds old Korean homes together.

The florals are arranged in hangari earthenware vessels traditionally used to ferment and preserve foods.

Photos provided by Thomas Mann House LA

Goethe Institut x Thomas Mann House LA

USC Libraries, the USC Dornsife Center for Advanced Genocide Research

Washington, D.C.

I was invited by the Goethe Institut to present my floral sculpture series for an event called “An Appeal to Reason” inspired by the life and influence of Thomas Mann as a lens that rooted conversations around the current state of democracy, importance of freedom of expression, and the role of artistic intervention.

what is something you always wished I had asked and knew about you? is a floral sculpture series that confronts how we hold and carry memory in the diaspora through cocoji — a fading practice of floral arranging in Korea lost during a time of occupation and war.

The figures in the series includes the last remaining photographic archives of my family originally from the Gwangju region of Korea. A region known for the student-led demonstrations in their fight for democracy against the coup of Chun Doo-hwan in 1980.

The gidung table crafted by artist Jeffrey Yoo Warren is built around a hanok joint using the same woodworking technique that holds old Korean homes together.

The florals are arranged in hangari earthenware vessels traditionally used to ferment and preserve foods.

Photos provided by Thomas Mann House LA

February 18-March 27, 2025

The Durational Performance of Cut Fruit

Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington x Amazon HQ2

Innovation Studio Residency

National Landing, VA

During my residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington x Amazon HQ2 Innovation Studio, I explored what natural preservation of unnatural objects look like for archiving memories of matrescence and embodied care.

Reimagining the art of air drying persimmons (gotgam in Korea) through clay, inherited gestures, and NFC tags, I dried over 50lbs of cut persimmons alongside clay sculpted persimmons. Visitors were invited to participate by creating their own clay persimmons and embedding them with a memory they carry for someone they love—recorded as a voicemail.

When a smartphone is placed near a clay persimmon, it activates a link allowing visitors to hear the story held within.

Illustrations by Echo Yun Chen

Workshop photographs courtsey of MoCa Arlington (National Landing, VA) and KID Museum (Bethesda, MD)

Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington x Amazon HQ2

Innovation Studio Residency

National Landing, VA

During my residency at the Museum of Contemporary Art Arlington x Amazon HQ2 Innovation Studio, I explored what natural preservation of unnatural objects look like for archiving memories of matrescence and embodied care.

Reimagining the art of air drying persimmons (gotgam in Korea) through clay, inherited gestures, and NFC tags, I dried over 50lbs of cut persimmons alongside clay sculpted persimmons. Visitors were invited to participate by creating their own clay persimmons and embedding them with a memory they carry for someone they love—recorded as a voicemail.

When a smartphone is placed near a clay persimmon, it activates a link allowing visitors to hear the story held within.

Illustrations by Echo Yun Chen

Workshop photographs courtsey of MoCa Arlington (National Landing, VA) and KID Museum (Bethesda, MD)

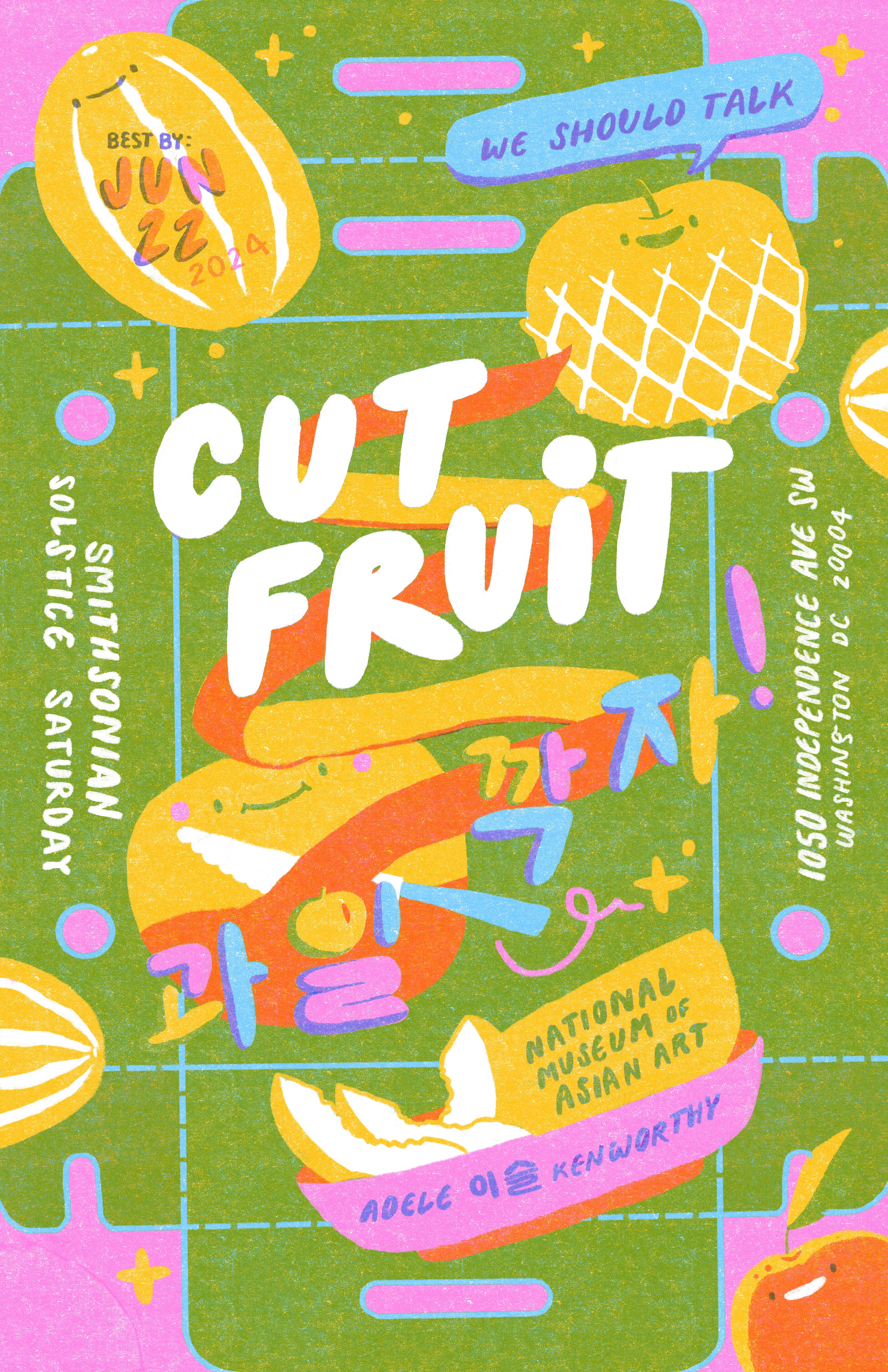

Smithsonian Summer Solstice Saturday

June 22, 2024

We Should Talk:

CUT FRUIT/과일깍자!

National Museum of Asian Art

Washington, D.C.

CUT FRUIT/과일까가! came to the National Museum of Asian Art in 100-degree weather with over 300lbs of Korean melons and Asian pears for their Smithsonian Solstice Saturday celebration. I was joined by artists Xena Ni and Thu Anh Nguyen as I cut fruit for hundreds of visitors and everyone came with the most incredible memories of love and care and visible hope.

For many Asian/Asian American family, fruit is shared as an act of love in abundance, often present at a child’s first birthday celebration in Korea, called a doljanchi; given in oversized boxes as housewarming gifts; and placed at altars for even our ancestors to enjoy.

Instead of price per pound signs, CUT FRUIT/과일깍자! invites us to carry the questions asked between the peels and slices:

what is the first taste you can remember?

what is something you always wished someone had asked and knew about you?

what fruit carries your favorite memories?

who is allowed to gather?

who is allowed rest?

You can learn more about this project at curiosityconnects.us/weshouldtalk

This project is the third installment of the We Should Talk series, created by Philippa Pham Hughes, Adele Yiseol Kenworthy, and Xena Ni. We Should Talk received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, and the American Women’s History Initiative Pool, administered by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.

Design by Ashley Wu

Illustrations by Kristin Tata

Poster by Echo Yun Chen

Photos of the performance taken on film by Lynn Le

CUT FRUIT/과일깍자!

National Museum of Asian Art

Washington, D.C.

CUT FRUIT/과일까가! came to the National Museum of Asian Art in 100-degree weather with over 300lbs of Korean melons and Asian pears for their Smithsonian Solstice Saturday celebration. I was joined by artists Xena Ni and Thu Anh Nguyen as I cut fruit for hundreds of visitors and everyone came with the most incredible memories of love and care and visible hope.

For many Asian/Asian American family, fruit is shared as an act of love in abundance, often present at a child’s first birthday celebration in Korea, called a doljanchi; given in oversized boxes as housewarming gifts; and placed at altars for even our ancestors to enjoy.

Instead of price per pound signs, CUT FRUIT/과일깍자! invites us to carry the questions asked between the peels and slices:

what is the first taste you can remember?

what is something you always wished someone had asked and knew about you?

what fruit carries your favorite memories?

who is allowed to gather?

who is allowed rest?

You can learn more about this project at curiosityconnects.us/weshouldtalk

This project is the third installment of the We Should Talk series, created by Philippa Pham Hughes, Adele Yiseol Kenworthy, and Xena Ni. We Should Talk received Federal support from the Asian Pacific American Initiatives Pool, administered by the Smithsonian Asian Pacific American Center, and the American Women’s History Initiative Pool, administered by the Smithsonian American Women’s History Museum.

Design by Ashley Wu

Illustrations by Kristin Tata

Poster by Echo Yun Chen

Photos of the performance taken on film by Lynn Le

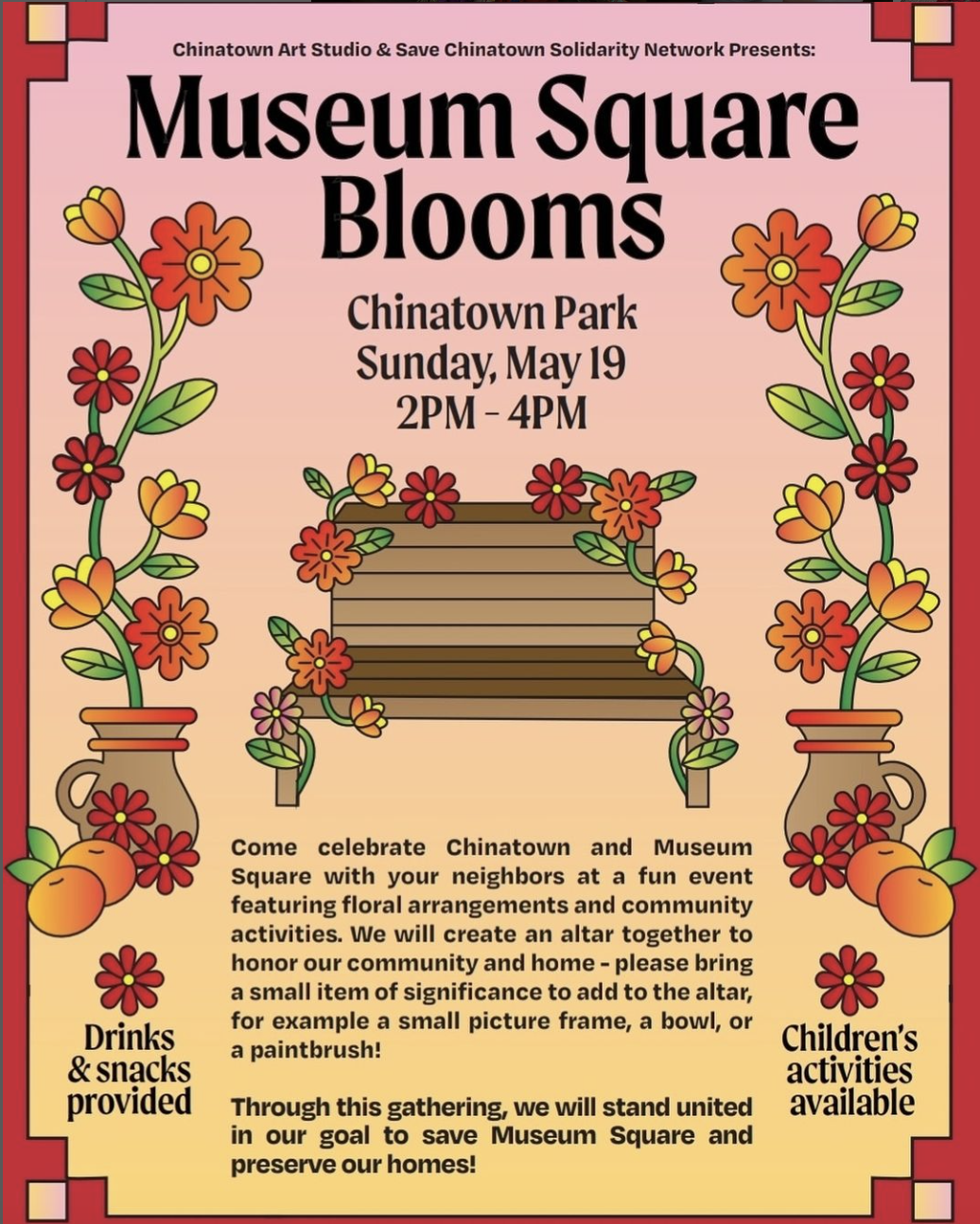

May 19, 2024

Museum Square Blooms

Chinatown Park

I St NW, Washington, DC

There are less than 300 Chinese residents remaining in DC’s Chinatown, many of them our elders and many of them facing active displacement. When Chinatown Arts Studio invited me to join their efforts to #savemuseumsquare without hesitation I said yes.

So much of my work in the last few years think a lot about what happens during occupation and war and what gestures and rituals we hold as places of comfort. And so the idea of home for me is more about how do I carry the memories of geographic longing that belong to my parents, how do I carry the ones that belong to me, and how do I carry both at the same time.

As the fight to preserve the history of Chinatown DC continues by protecting the remaining living residents now, instead of this practice of asking Where are you from? Where are you really from? What is your name? What is your real name?

We can ask:

Where do you claim? What claims you?

How do you carry memories of home?

How do you long to be remembered?

Whose stories do you carry?

Thank you to the organizers for doing the real work, for the opportunity to witness and support, and for believing art and flowers can nourish movements like this.

Immense gratitude for the floral support from Flowers By MJ.

This event was funded in part by the Awesome Foundation.

Visit www.SaveChinatownDC.org to learn more.

Photos provided by Save Chinatown DC

Chinatown Park

I St NW, Washington, DC

There are less than 300 Chinese residents remaining in DC’s Chinatown, many of them our elders and many of them facing active displacement. When Chinatown Arts Studio invited me to join their efforts to #savemuseumsquare without hesitation I said yes.

So much of my work in the last few years think a lot about what happens during occupation and war and what gestures and rituals we hold as places of comfort. And so the idea of home for me is more about how do I carry the memories of geographic longing that belong to my parents, how do I carry the ones that belong to me, and how do I carry both at the same time.

As the fight to preserve the history of Chinatown DC continues by protecting the remaining living residents now, instead of this practice of asking Where are you from? Where are you really from? What is your name? What is your real name?

We can ask:

Where do you claim? What claims you?

How do you carry memories of home?

How do you long to be remembered?

Whose stories do you carry?

Thank you to the organizers for doing the real work, for the opportunity to witness and support, and for believing art and flowers can nourish movements like this.

Immense gratitude for the floral support from Flowers By MJ.

This event was funded in part by the Awesome Foundation.

Visit www.SaveChinatownDC.org to learn more.

Photos provided by Save Chinatown DC